Steelers loved and lost: memorializing Mike Webster

While the history behind Memorial Day in the United States is not clear as to the date or place of origin, and the tradition has become a day for Americans to remember and honor loved ones who have passed — both while serving in the armed forces and those who have not – a few of us at Steel City Underground were talking about Pittsburgh Steelers players we, as fans, have loved and who are lost to us in death, but not in our memories or our hearts. I mentioned that I had an emotional experience in contacting Hall of Fame center Mike Webster, and was encouraged to share. So, on this Memorial Day, I chose to share my own commemoration to a guy who made a strong impact on me as a Steelers fan.

Webster was a Midwest kid. I could relate to his background of growing up on a potato farm in Wisconsin, not because I was raised on a farm, but because I was raised in nearby Iowa. Wrestling and football, two sports Mike participated in during high school, were big draws in Iowa as well. I’m not sure what life was like near Tomahawk, but I’m sure that playing sports was a way to stand out as a high-schooler in Wisconsin just like it was in Iowa. And the kids that grew up on farms typically had a work ethic that rivaled most they played with.

When Webster was drafted out of the University of Wisconsin in 1974, I was barely old enough to walk over to the television. Born two decades before I was, some may express that they aren’t sure how Webster – as a player – could influence me in any way since I must be too young to remember him on the field. Thankfully, my maternal grandfather was a big reason I was exposed to “Iron Mike” (long before Mike Tyson ever thought to use the moniker), his No. 52 jersey, and some of the greatest Steelers football to ever be played.

My grandfather loved to watch sports, and I was his ‘football buddy’. He’d sit in his leather recliner, me on his lap, with a bowl of homemade popcorn grandma would do in a skillet (smothered in butter, of course) and watch the games every weekend during the season. One fine day, my grandpa asked me which team I was going to root for. I don’t remember who the opposing team was, but I picked the Pittsburgh Steelers, and that began my love for the team. Around the age of five, I got my first jersey – No. 12 Terry Bradshaw. I can’t say that I didn’t choose the Steelers because the Iowa Hawkeyes had the same jerseys; it’s possible that influenced my decision on who to cheer for that day. Over time, however, I never wavered from choosing them every single time they played and grandpa had to choose the opponent (he liked to pretend we were betting on the outcome).

Part of Bradshaw’s success, however, was due to big No. 52. I’d watch as Webster would snap the ball and then manhandle defensive linemen as Terry scrambled around in the backfield looking for a target – Lynn Swann, John Stallworth – or hand the ball off to Franco Harris. To me, the Steelers were larger than life and giants on the football field.

My grandpa also started another lifelong hobby for me that was related to the Steelers as well. He’d always buy me a few packs of Topps football cards – the kind with the strip of gum inside – and my favorite thing was ripping off the wrapper to see which Steelers would be inside. Over the years, I’ve amassed thousands and thousands of cards. One of my favorite “pulls” were rookie cards of ‘Mean’ Joe Green and Harris, but I was fortunate to also open that wax paper and find Webster in more than one pack over those early years.

I was not a Pittsburgh native, so I was unaware of the tragic life Webster was leading. His wife, Pamela, recalled in a Reader’s Digest article (March 2003, Game Over) how her husband became a hard-working, play-with-pain member of the Steelers by saying, “Mike would be the first one at the stadium and the last to leave, he was so afraid to fail.” Through my eyes, all I saw was a guy who was a hero to me. “You look at the center position as the foundation,” fellow Hall of Fame Steeler running back Franco Harris said in the same article. “Mike was a guy you could always count on.” I would watch Webster slam into player after player to keep Pittsburgh marching down the field, his helmet colliding with those of defenders, and never thought anything more than that Webster was one of the toughest guys I’d seen play the game.

When Webster was signed by the Kansas City Chiefs, he was closer to my home and I got to see his last games in the NFL. I still cheered him on, even though it wasn’t the same seeing him in a jersey that wasn’t black and gold. He retired on March 11, 1991, as the last active player in the NFL to have played on all four Super Bowl winning teams of the 1970s Steelers. He’d played more seasons as a Pittsburgh Steelers than anyone else in franchise history until Ben Roethlisberger tied the record in 2018 (and will break it in 2019).

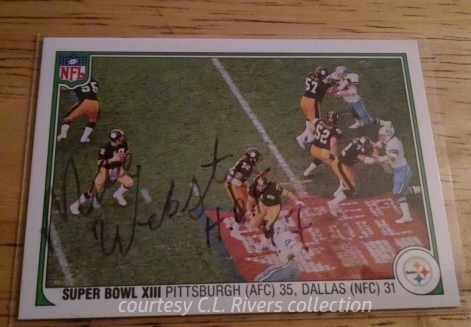

Before the days of big-money autograph sessions and companies that sell opportunities to get items signed, I would mail some of the cards I’d collected to players with a small note telling them why I appreciated their play and why I wanted to add their autograph to a growing collection of Steelers cards.

When “Iron Mike” got inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1997, I was moved by the fact that Bradshaw presented for Webster, that the two men still had a bond after all those years of playing football. I sent a letter and cards to Mike via the Hall of Fame and was pleased to get back all three, signed, even though I had asked him to keep at least one of them for his family.

I had no idea that Webster was looking into the abyss and the abyss was looking back at him, however. I didn’t realize that the years of playing hard had taken their toll on him as a man, as a father, as a husband. I wasn’t aware that he’d often leave Lodi (WI) and travel back to Pittsburgh, sometimes being in a homeless state as he withdrew from his family and society. That Webster sent me back signed cards as he struggled with the after-effects of the game and his departure from the man he had been is, in itself, a bit of a heartbreaking honor to me.

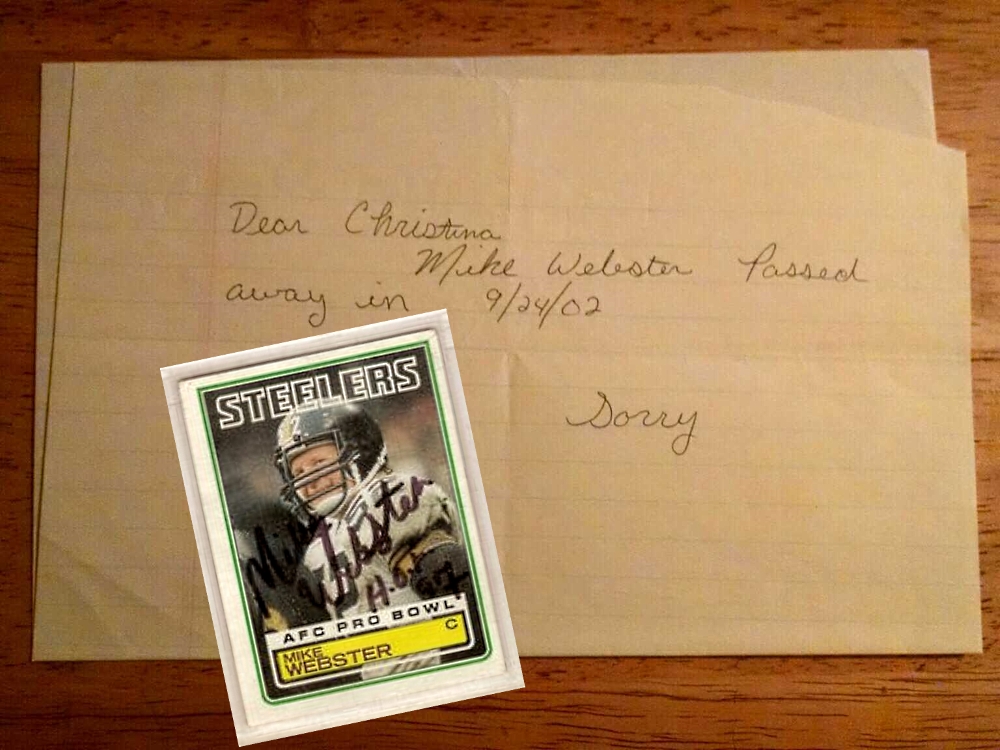

Late in 2002, I sent another letter and card to Webster via the Hall of Fame. What I received back was even more heartbreaking.

I can only assume that Pamela had been fielding mail sent for Mike and that she’d had the difficult task of returning ‘fan mail’ to many people. When I read the enclosed letter (the card you see in the picture was sent to me previously from Webster), I honestly sat and cried. I thought about how a hero of mine had passed but also how a family had lost a father and husband, how the city of Pittsburgh and Steelers fans had lost an icon. When I learned more about Mike’s final days, though, the letter became a reminder to me of how much a player gives to be on the big stage. In Webster’s case, he gave everything – and unfortunately, no one knew the cost could be so severe.

I have kept the letter and the cards that Webster was so kind to sign in a special collection. They aren’t in with the over 100 autographed NFL and Steelers player cards. In a special spot, protected by acid-free plastic, sealed except to show others on special occasions, I keep Webster’s items apart. His items are joined only by an autographed card and a brief note from Dan Rooney. They stay there to remind me that heroes are human; they bleed, hurt, ache, laugh, love and pass on from this life like the rest of us. The memories they give us are forever.

On this day, I know there are many fans who have Steelers players they’ve loved and lost. I encourage all who love the game, love the team, to give a moment of silence and think about the players as human beings – in all their glory and faults – and smile at the times they offered something on the field as well.

We may offer our own memorials for loved ones and those we’ve known who’ve fought for freedom or in battles far from home, but I hope we have our individual moments where we celebrate the lives of men who showed heart when they stood at the 50-yard line and gave us a part of themselves that we often don’t appreciate until they’ve moved on as well.